News

Use cases

Social media and other online scraping

Social media is part of almost everyone’s lives. When you put photos or videos online, you probably imagine that your friends, your family and your followers will see them. You probably don’t imagine that they will be taken and processed by shady private companies and used to train algorithms. You’re probably even less likely to imagine that this information could be kept in a massive biometric database, and even used by police to identify you after you were in the area of a protest or were walking through a zone secretly surveilled.

WHAT is scraping?

Social media Scraping is the process of gathering data automatically. Now you might wonder, what type of data can they get from social media? Well, the data can go from usernames or followers to very sensitive data, like where do you live and … your biometric data such as your facial features. This is generally performed by bots and can gather and process large amounts of data in very little time.

While it might seem like we are far away from that, this is happening now, right in our faces.

Scraping is happening already

Probably the most well-known cuplrit of mass social media scraping of our faces is the notorious ClearviewAI. In this case, just being in the background of a friend’s photo that gets uploaded to the internet could be enough for you to end up in ClearviewAI’s 3 billion photo database. Yes, that’s billion with a “b”. Services like the ones kindly offered by the likes of CleaviewAI have been used for biometric mass surveillance practices by police forces all around the EU and elsewhere in the world.

Gladly, thanks to the efforts of one of the ReclaimYourFace’s campaigners, the inclusion of images of people in the EU in the ClearviewAI database has already been proven to be illegal. However, that hasn’t stopped it from happening.

Another well-known case is the one from Poland-founded company PimEyes (who suddenly relocated to the Seychelles, allegedly to avoid regulatory scrutiny in the EU). This is another company offering similar services – although they claim that it is not social media sites that they scrape but other sites (as if that made it more ethical!). However, unlike ClearviewAI, which tends to offer their services to law enforcement, PimEyes are offered to any individual that would like to access it.

Yes, anyone walking on the street could scan your face and know everything about you.

Just imagine if wherever you went, any person could know your name, your interests, where you live and many other sensitive things about you just by scanning your face at a distance using their phone. You might not even know that they had done this – but they would be able to know a lot about you.

I don’t use social media

Even if you don’t use social media, you can still be part of those databases. For instance, if people that you know have uploaded pictures with you in them to social media giants like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, or if you use certain other online services with your picture, your biometric data could be scraped. And yes, these Big Tech companies will know probably as much as if you were a social media user. In fact, there have even been reports of so-called ‘shadow profiles’, where Facebook knows so much information about people who don’t have accounts that it’s as if they have an active profile!

Why do we need to stop this?

Summarise harms and the need to stop. Harms connect to bigger things than privacy ad anonymity e. g. stalkers, ex partners, being judged by authorities based on social media posts, etc…

Examples

PimEyes is a company with an enormous facial recognition database, reportedly scraped from the internet without people’s knowledge, and available for members of the public to use to spy on whoever they like: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/05/04/tech/pimeyes-facial-recognition/index.html

Not only did Clearview AI illegally scrape our biometric data from social media, the safety of this data has been compromised in past years. All of our data is not only used against us by police forces around the world, but now leaked to anyone else: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/02/26/tech/clearview-ai-hack/index.html

News and reports

Read our News Section to learn our latest updates, and SIGN the ECI!

Borders, migrants and failed humanitarism

Some of the most chilling biometric systems we have seen are those deployed against people on the move.

Whether it’s for migration, tourism, to see their family, for work, or to seek asylum, people on the move rely on border guards/police and governments to grant them permission to enter.

It should be obvious that they have a right to be treated humanely and with dignity while doing so. However, we know that non-EU nationals traveling into the EU are frequently treated as a frontier for experimentation with biometric technologies.

Governments and tech companies exploit their power to treat people on the move as lab rats for the development of invasive technologies under the guise of “innovation” or “security”. These, sometimes, are subsequently deployed as part of general monitoring systems.

Experimenting on people on the move

The authorities and companies that are deploying these technologies exploit the secrecy and discretion that surrounds immigration decisions. In result, they experiment with technologies that are worryingly pseudo-scientific and with some that rely on discredited and harmful theories like phrenology.

For instance, real examples from Europe include:

1. The analysis of people’s “micro-expressions” to supposedly detect if they are lying

2. Testing on voices and bones as a way to interrogate their asylum claims.

Experimenting on: people in need of humanitarian aid

Similar patterns to border administration are increasingly being seen in the humanitarian aid context. Aid agencies or organisations sometimes see biometric identification systems as a silver bullet for managing complex humanitarian programmes without properly assessing the risks and the rights implications. This is often driven by the unrealistic promises made by biometric tech companies.

In the context of humanitarian action, people who are relying on aid are rarely in a position to refuse to provide their biometric data, meaning that any ‘consent’ given cannot be considered legitimate.

Therefore, their acceptance could never form a legal basis for these experiments, because they are forced by the circumstance to accept. For people who are not in this position, it would never be legal to act in this way. In humanitarian aid, people’s fragility is exploited. There are also major concerns about how such data are stored. For instance, there are still many questions about how it may be used in ways that are actually incredibly harmful to the people they are claiming to help. If these concerns were not enough, such practices also have a high chance of leading to mass surveillance and other rights violations by creating enormous databases of sensitive data.

WHY SHOULD WE FIGHT BACK?

Not only are these unreliable tests often unnecessarily invasive and undignified, but they treat people who are in need of protection instead as if they are liars, test subjects, or intrinsically suspicious just for being a migrant.

Further more, EU and EU countries fund heavily this. A lot of the money that goes into funding these projects comes from EU agencies or Member States, for example through the EU’s Horizon2020 programme. In their public database, you can read about how EU money is funding biometric experiments that would not be out of place in a science fiction film.

This is happening in tandem with a rise in funding for the EU’s Frontex border agency, which has been accused of violently militarising European borders and persecuting people on the move.

Examples

In Italy, the police have used biometric mass surveillance against people at Italy’s borders and have attempted to roll out a real-time system to monitor potentially the whole population with the aim of targeting migrants and asylum seekers: https://reclaimyourface.eu/chilling-use-of-face-recognition-at-italian-borders-shows-why-we-must-ban-biometric-mass-surveillance/

In the Netherlands, the government has created a huge pseudo-criminal database of personal data which can be used for performing facial recognition solely for the reason that those people are foreign: https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/EDRI_RISE_REPORT.pdf [p.67]

In Greece, the European Commission funded a notorious project called iBorderCTRL which used artificial intelligence and emotion recognition to predict whether people in immigration interviews are lying or not. The project has been widely criticised for having no scientific basis and for exploiting people’s migration status to try out untested technologies: https://iborderctrl.no/

News and reports:

Learn more about the different ways that biometric mass surveillance affects us, and SIGN the ECI!

Predictive Policing: Repeating history through algorithms

Certain groups, such as racialised people, face disproportionate levels of police intervention and police violence in Europe and across the world. It is not surprising then, that the police forces’ uptake of new technologies follows the same patterns.

Many of the most high-profile discriminatory examples of facial recognition have been in the US. However, the EU is not without its share of examples of how predictive policing + biometric analysis = a perfect storm of unlawful police discrimination.

Worse still, automated predictive policing is often hidden behind a false claim that technology is neutral and excuses from police forces evading accountability: “The tech told me to do it!”.

Analog predictive policing

A common justification given by governments to explain the over-policing of racialised people is that racialised communities are inherently more criminal. They claim that this is supported by statistics showing that racialised people are more frequently arrested and imprisoned. . However, the only thing that these historical statistics highlight is, in fact, that racialised communities are vastly over-exposed to (often violent) police intervention, and are systematically treated more harshly and punitively by criminal justice systems. These statistics reflect on the actions of police and of justice systems, not on the behaviours or qualities of racialised people.

Systemic discrimination is rooted in analogue predictive policing practices: police (and wider society) making judgements and predictions about an individual based on, for instance, the colour of their skin or the community of which they are a part.

The use of new technologies by police forces makes these practices even more harmful to people’s lives, while hidding under the false pretext of “technological objectivity”.

Automated predictive policing: WHAT is it and HOW is it used?

Automated predictive policing is the practice of applying algorithms on historical data to predict future crime. This could be by using certain group factors (such as someone’s ethnicity, skin colour, facial features, postcode, educational background or who they are friends with) to automatically predict whether they are going to commit a crime.

There is a principle sometimes referred to as “Garbage in, garbage out”. This idea means that if you feed an algorithm with data that reflects bias and unfairness, the results you get will always be biased and unfair.

“Garbage in, garbage out” guides some of the ways law enforcements uses automated predictive policing when:

- Deciding where to deploy extra police presence. This traps communities that have been over-policed in an inescapable loop of more and more police interventions;

- Predicting whether people are likely to re-offend, an assesment that can influence whether someone gets parole or not. This means that a person’s liberty is decided based on discriminatory data about other people that the system thinks are similar to that person.

WHY we must FIGHT BACK?

Having certainties in life can be comforting for all of us. However, when the police and the criminal justice system tries to predict crime, it is not possible to know with enough certainty how someone is going to act in the future. Trying to do so will only reinforce and intensify historical patterns of injustice and grow societal inequalities. Introducing algorithmic predictions in policing will only make the poor poorer, the excluded left out of society and those suffering from discrimination, even more discriminated.

As unique humans, with free will, self-determination and the power to change our life path, we have the right to be treated fairly and not punched down by (automated) justice system.

Examples

In the Netherlands, “smart” devices have sprayed the scent of oranges at people that the biometric algorithm thinks are displaying aggressive behaviour. Given the biases and discriminatory assumptions baked into such tech, it is likely that such technologies will disproportionately be used against racialised people. Being followed by the smell of oranges might not seem so bad – but this tech is also being used in the Netherlands to trigger the deployment of an emergency police vehicle responding to what the algorithm predicts is a violent incident: https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/EDRI_RISE_REPORT.pdf [p.92]

In Sweden, the police were fined for using unlawful facial recognition systems, and were particularly criticised for failing to undertake any assessment of how it might infringe on people’s rights to data protection and related rights, such as equality: https://edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2021/swedish-dpa-police-unlawfully-used-facial-recognition-app_en

In the Italian city of Como, authorities deployed biometric surveillance systems to identify ‘loitering’ in a park in which stranded migrants were forced to sleep after being stopped at the Swiss-Italian border: https://privacyinternational.org/case-study/4166/how-facial-recognition-spreading-italy-case-como

A Spanish biometric mass surveillance company called Herta Security – which has received funding from the EU – developed facial recognition technology which they say can profile people’s ethnicity. When we challenged them about this being unlawful, they said it isn’t a problem because they would only sell that part of their tech to non-EU countries: https://www.wired.com/story/europe-ban-biometric-surveillance/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u30vRl70tgM&feature=youtu.be

News and reports:

January 2020:

Learn more about the different ways that biometric mass surveillance affects us, and SIGN the ECI!

From biometric IDs to biometric mass surveillance

We might not even know it, but most of us will have already encountered biometric databases in practice. There are already many databases in the EU, containing faces, fingerprints and other biometric data of millions and millions of people.

One of the ways that governments get this data is by making it necessary for people to submit their sensitive biometric data in order to get an identity card. In some countries, these identity cards are even essential for accessing public services. This means that if you disagree with giving away data that can identify you forever, you could be excluded from hospitals, schools, or even accessing basic services such as electricity or water!

Is a Biometric ID also biometric mass surveillance?

Biometric mass surveillance is a set of practices that use technological tools to analyse data about people’s faces, bodies and behaviours in a generalised or arbitrarily-targeted way, in publicly-accessible spaces. It can be done in different ways, but it always requires some sort of data to perform a comparison.

For example, in the process of biometric identification, an anonymous person will be scanned and matched against an existing database of images of people. In this way, the system will verify whether or not the anonymous person matches anyone in the database. This means that a biometric database is needed in order for the system to be able to identify people. For this reason, biometric databases can form an essential component of biometric mass surveillance infrastructure.

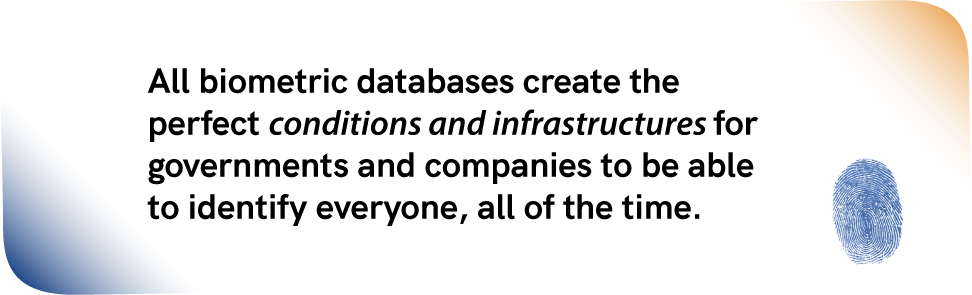

Not all biometric databases automatically equal biometric mass surveillance. However, all biometric databases create the perfect conditions and infrastructures for governments and companies to be able to identify everyone, all of the time.

This is problematic because of the potential for mass surveillance, which has already been enabled in some examples listed below. More, centralising the collection of such sensitive data opens the door to abuses, leaks or hacks, and threats to people’s safety.

Are biometric databases already turned into an infrastructure for biometric mass surveillance?

These data bases are already being used for mass surveillance purposes. These are just some examples:

- Some EU institutions have been pushing to expand the already large biometric databases that are held on asylum seekers and migrants – which comes with its own particular set of risks [hyperlink to use case about borders and migration].

- Some governments use databases that they have created themselves – whether for a national digital ID or for another purpose – which allows them to collect together vast amounts of sensitive data about their citizens.

- Other governments also buy access to databases from private companies (like the notorious ClearviewAI), which can give these companies access to sensitive data and influence over how states analyse and use that data.

- Also some private companies, like supermarkets, create their own databases, for example to keep track of people that they suspect of shoplifting. This is especially troubling because people are added to this database based solely on the suspicions of a security guard or shopkeeper, without any due process. People could find themselves excluded from shops without any judicial review, as well as as a result of having been unfairly profiled.

Examples

In Poland, children as young as 12 have been required to submit their biometric data to the government, which will form a permanent record of them and creates the potential for mass surveillance: https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/EDRI_RISE_REPORT.pdf pp.118-122

In the Netherlands, 180,000 people are falsely included in the government’s criminal database which is used to perform facial recognition analysis, and 7 million people are included in another biometric database simply for being foreign: https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/EDRI_RISE_REPORT.pdf

In Italy, the police’s SARI database has been used extensively to undertake biometric surveillance and attempts have been made to get permission to use the system in its ‘real-time’ (i.e. mass surveillance) mode. A staggering 8 out of 10 people in the system’s reference database are foreigners: https://edri.org/our-work/face-recognition-italian-borders-ban-biometric-mass-surveillance/

In Greece, the police have set up a mass central biometric database containing fingerprints and facial images of all Greek passport holders, likely without a legal basis (as biometric data from people’s passports is legally supposed to be stored on the passport itself, not in a database): https://edri.org/our-work/reclaim-your-face-update/

In Sweden, the police have been fined for illegally using ClearviewAI’s database: https://edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2021/swedish-dpa-police-unlawfully-used-facial-recognition-app_en

In France, the police have been using the enormous ‘TAJ’ database of 8 million images of people involved in police investigations (including people that have been acquitted): https://edri.org/our-work/our-legal-action-against-the-use-of-facial-recognition-by-the-french-police/

News and reports:

September 2021

Learn more about the different ways that biometric mass surveillance affects us, and SIGN the ECI!

Biometric mass surveillance as general monitoring

Digital technologies make general monitoring of people easier, but these practices have been around for a long time. Infamous surveillance societies throughout history and today have used general monitoring as a way to keep tabs on populations: think the East Germany Stasi or the way in which the government in China surveil the population.

This may sound extreme – but real examples that are appearing across Europe have a lot more in common with these regimes than you might.

So, WHAT IS GENERAL MONITORING?

When we say general monitoring, we’re talking about the use of surveillance devices to spy on every person in a generalised manner.

This could be, for example, by using a camera in a public space (like a park, a street, or a train station). It can also happen in other ways, for example when governments or companies listen in to everyone’s phone calls, or snoop on everyone’s emails, chats, and social media messages.

That’s why another term for general monitoring is mass surveillance.

But why is that harmful?

General monitoring is harmful because it prevents us from enjoying of privacy and anonymity. These democratic principles are incredibly important as they enable us to live our lives with dignity and autonomy.

Depriving people from anonymity and privacy can have real and serious impacts: imagine governments and companies knowing all of your health problems because they’ve tracked which medical establishments you go to over time. I

Imagine being surveilled because you were seen going to an LGBTQ+ bar – especially if you live in a country where LGBTQ+ people do not enjoy full rights. Imagine your future life prospects (e.g. work, university) being limited because you were caught loitering or littering as a teenager.

Another reason why general monitoring is dangerous is because it alters the justice systems and the principles governing it – such as “innocent until proven otherwise”. If governments want to watch us, they are supposed to have a proper and well-justified reason for doing so, because we all have a right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. With general monitoring, this is flipped on its head: every single person in a particular group or a whole population is treated as a potential suspect.

Below, you can find evidence of biometric systems in the EU watching people for all of these reasons. This only gives us a hint of how this data might be used in the future.

Examples

In the German city of Cologne, hundreds of thousands of people have been placed under biometric surveillance outside LGBTQ+ venues, places of worship and doctors’ surgeries: “The rise and rise of biometric mass surveillance in the EU” [p.20].

Across Europe, people exercising their right to peaceful assembly have been targeted through general biometric monitoring in at least Germany, Austria, Slovenia, the UK, and Serbia, and the French government have also attempted to do this as well. It’s not just streets – we’ve seen similar systems in train stations (Germany), airports (Belgium), football stadiums (Denmark and the Netherlands) and much more.

In the Netherlands, three cities have been turned into ‘Living Labs’ where the general monitoring of people’s biometric data is combined with general monitoring of their social media interactions and other data, creating profiles which are then used to make decisions about their lives and futures: The rise and rise of biometric mass surveillance in the EU” [p.88]

In Greece, the European Commission’s Internal Security Fund gave €3 million to private company Intracom Telecom to develop facial recognition for police to use against suspects, witnesses and victims of crime: https://edri.org/our-work/facial-recognition-homo-digitalis-calls-on-greek-dpa-to-speak-up/

In Czechia, the police bought Cogniware facial recognition software that can predict emotions and gender and according to Cogniware’s website, has the capacity to link every person with their financial information, phone data, the car one drives, workplace, work colleagues, who they meet, places they visit and what they buy: https://edri.org/our-work/czech-big-brother-awards-worst-privacy-culprits/

News & reports

May 2020:

In collaboration with our campaign partners:

Reclaim Your Face is also supported by:

MEP Patrick Breyer, Germany, Greens/EFA

MEP Marcel Kolaja, Czechia, Greens/EFA

MEP Anne-Sophie Pelletier, France, The Left

MEP Kateřina Konečná, Czechia, The Left

Should your organisation be here, too?

Here's how you can get involved.

If you're an individual rather than an organisation, or your organisation type isn't covered in the partnering document, please get in touch with us directly.

Reclaim Your Face is also supported by:

MEP Patrick Breyer, Germany, Greens/EFA

MEP Marcel Kolaja, Czechia, Greens/EFA

MEP Anne-Sophie Pelletier, France, The Left

MEP Kateřina Konečná, Czechia, The Left

Should your organisation be here, too?

Here's how you can get involved.

If you're an individual rather than an organisation, or your organisation type isn't covered in the partnering document, please get in touch with us directly.