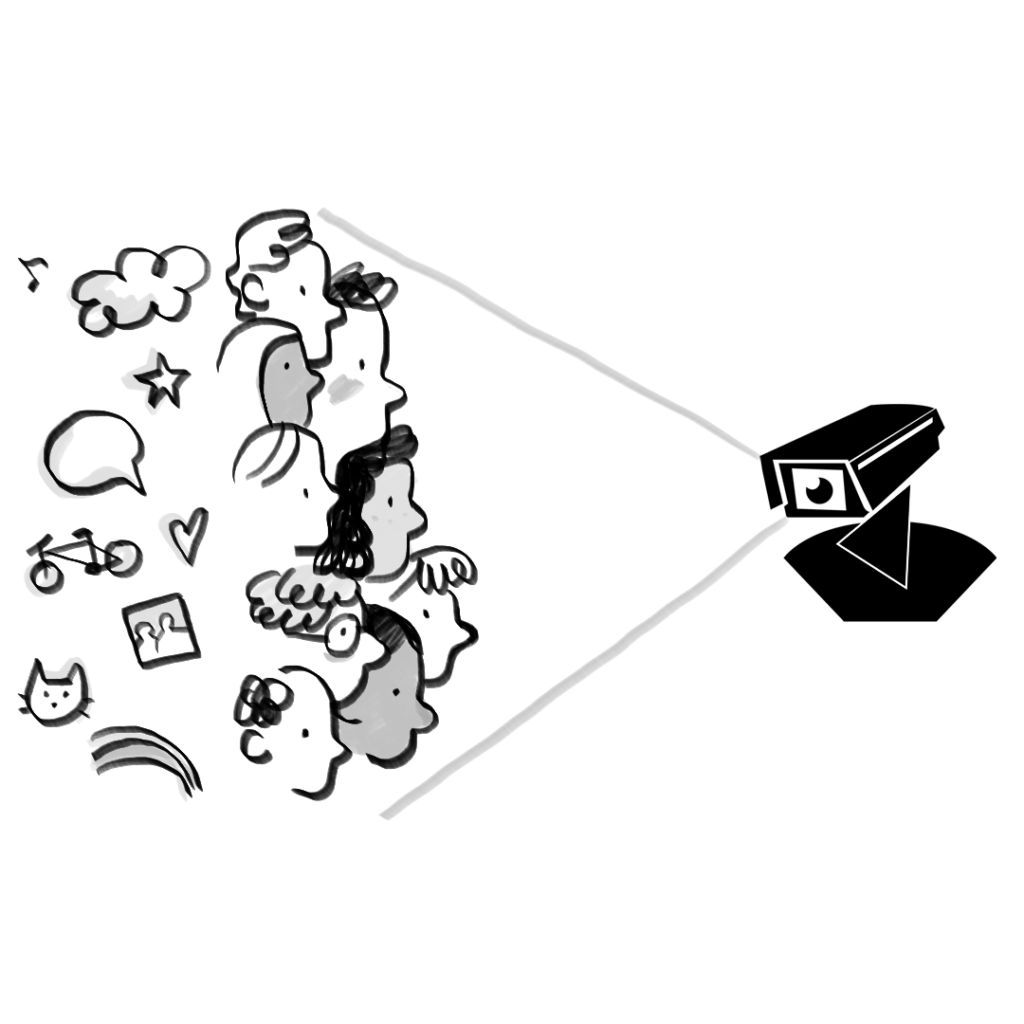

Certain groups, such as racialised people, face disproportionate levels of police intervention and police violence in Europe and across the world. It is not surprising then, that the police forces’ uptake of new technologies follows the same patterns.

Many of the most high-profile discriminatory examples of facial recognition have been in the US. However, the EU is not without its share of examples of how predictive policing + biometric analysis = a perfect storm of unlawful police discrimination.

Worse still, automated predictive policing is often hidden behind a false claim that technology is neutral and excuses from police forces evading accountability: “The tech told me to do it!”.

Analog predictive policing

A common justification given by governments to explain the over-policing of racialised people is that racialised communities are inherently more criminal. They claim that this is supported by statistics showing that racialised people are more frequently arrested and imprisoned. . However, the only thing that these historical statistics highlight is, in fact, that racialised communities are vastly over-exposed to (often violent) police intervention, and are systematically treated more harshly and punitively by criminal justice systems. These statistics reflect on the actions of police and of justice systems, not on the behaviours or qualities of racialised people.

Systemic discrimination is rooted in analogue predictive policing practices: police (and wider society) making judgements and predictions about an individual based on, for instance, the colour of their skin or the community of which they are a part.

The use of new technologies by police forces makes these practices even more harmful to people’s lives, while hidding under the false pretext of “technological objectivity”.

Automated predictive policing: WHAT is it and HOW is it used?

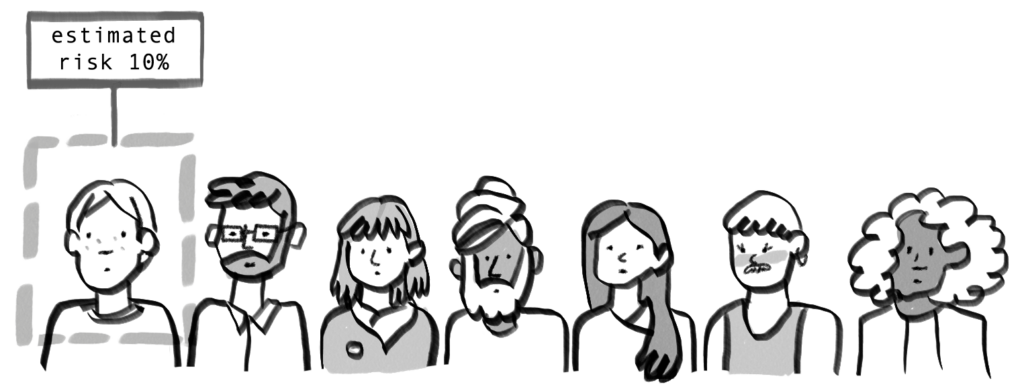

Automated predictive policing is the practice of applying algorithms on historical data to predict future crime. This could be by using certain group factors (such as someone’s ethnicity, skin colour, facial features, postcode, educational background or who they are friends with) to automatically predict whether they are going to commit a crime.

There is a principle sometimes referred to as “Garbage in, garbage out”. This idea means that if you feed an algorithm with data that reflects bias and unfairness, the results you get will always be biased and unfair.

“Garbage in, garbage out” guides some of the ways law enforcements uses automated predictive policing when:

- Deciding where to deploy extra police presence. This traps communities that have been over-policed in an inescapable loop of more and more police interventions;

- Predicting whether people are likely to re-offend, an assesment that can influence whether someone gets parole or not. This means that a person’s liberty is decided based on discriminatory data about other people that the system thinks are similar to that person.

WHY we must FIGHT BACK?

Having certainties in life can be comforting for all of us. However, when the police and the criminal justice system tries to predict crime, it is not possible to know with enough certainty how someone is going to act in the future. Trying to do so will only reinforce and intensify historical patterns of injustice and grow societal inequalities. Introducing algorithmic predictions in policing will only make the poor poorer, the excluded left out of society and those suffering from discrimination, even more discriminated.

As unique humans, with free will, self-determination and the power to change our life path, we have the right to be treated fairly and not punched down by (automated) justice system.

Examples

In the Netherlands, “smart” devices have sprayed the scent of oranges at people that the biometric algorithm thinks are displaying aggressive behaviour. Given the biases and discriminatory assumptions baked into such tech, it is likely that such technologies will disproportionately be used against racialised people. Being followed by the smell of oranges might not seem so bad – but this tech is also being used in the Netherlands to trigger the deployment of an emergency police vehicle responding to what the algorithm predicts is a violent incident: https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/EDRI_RISE_REPORT.pdf [p.92]

In Sweden, the police were fined for using unlawful facial recognition systems, and were particularly criticised for failing to undertake any assessment of how it might infringe on people’s rights to data protection and related rights, such as equality: https://edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2021/swedish-dpa-police-unlawfully-used-facial-recognition-app_en

In the Italian city of Como, authorities deployed biometric surveillance systems to identify ‘loitering’ in a park in which stranded migrants were forced to sleep after being stopped at the Swiss-Italian border: https://privacyinternational.org/case-study/4166/how-facial-recognition-spreading-italy-case-como

A Spanish biometric mass surveillance company called Herta Security – which has received funding from the EU – developed facial recognition technology which they say can profile people’s ethnicity. When we challenged them about this being unlawful, they said it isn’t a problem because they would only sell that part of their tech to non-EU countries: https://www.wired.com/story/europe-ban-biometric-surveillance/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u30vRl70tgM&feature=youtu.be