In May 2024, EDRi member Access Now’s Caterina Rodelli travelled across Greece to meet with local civil society organisations supporting migrant people and monitoring human rights violations, and to see first-hand how and where surveillance technologies are deployed at Europe’s borders.

Pushback practices have been recorded in Evros since the late 1980s

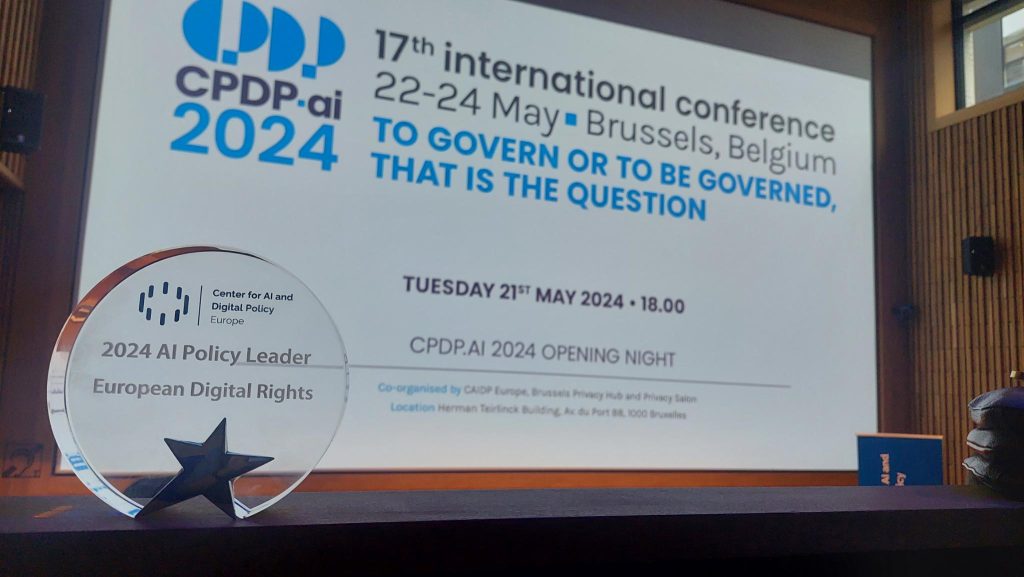

In the second installment of a three-part blog series, EDRi member Access Now’s Caterina Rodelli explains how EU-funded research projects on border surveillance are legitimising violent migration policies. Catch up on part one here.

As I drove along Greece’s E85 highway from the coastal city of Alexandroupoli towards the northernmost city of Orestiada, a grey wall appeared as I passed the small town of Soufli, known for its silk industry. The more I drove northwards, the more the wall unravelled itself, its sharpened edges and surveillance towers spreading down the road.

This wall runs along the Evros river, which marks the 200 kilometre natural border between Türkiye and Greece. It was first built in 2011 as a wire fence, after the Greek government, inspired by the US-Mexico border, ordered its construction as a purported solution to keep out migrants seeking safety. Other walls have since been erected in the Evros region; physical manifestations of the “embeddedness and longevity of border violence.” Pushback practices — i.e. the informal and illegal expulsion of people across borders without due process — have been an integral element at many European borders since the early 2000s and have been recorded in Evros since the late 1980s.

Human rights groups, journalists, and researchers have documented several instances of abuse with sometimes fatal consequences

Human rights groups, journalists, and researchers have documented several instances of abuse in this part of Greece: from trapping people in houses where they are subjected to degrading and violent treatment and pushing back migrants with sometimes fatal consequences, including the reported drowning of a four-year-old child, to instances of sexual assault.

Moreover, both migrants and those who defend their rights have been targeted with multiple smear campaigns, including one that blamed migrants for sparking wildfires that devastated more than 3002 miles of land in 2023.

Meanwhile in the same region, the EU has been a long-time supporter of multiple research projects on border surveillance. As part of the now-defunct Horizon 2020 and ongoing Horizon Europe schemes, the EU has funded programmes testing integrated advanced border surveillance technologies, such as thermal imaging cameras, radio frequency analysis systems, mobile unmanned vehicles (including drones, and autonomous ground / sea vehicles), or pylons mounted with tracking sensors.

Researcher Lena Karamanidou has been monitoring the development of these research projects, specifically in the Evros river’s delta, as part of the Border Violence Monitoring Network’s (BVMN) work on border surveillance technologies. They have found evidence that two Horizon 2020 projects, Nestor and Andromeda, have been tested in the area and used by local police authorities for real-life border control activities, outside of the research framework. These projects, which claimed to improve border surveillance solutions, were implemented by a pan-European consortium of public bodies, private companies, and research institutes. Nestor focused on testing the “next generation holistic border surveillance system providing pre-frontier situational awareness beyond maritime and land border areas,” while Andromeda tested solutions for improving information sharing among authorities engaged in border management.

The research projects in the Evros area raise two important questions

The roll-out of these research projects in the Evros area, where violence against migrant people is a near daily occurrence, raise two important questions:

- What exactly does the EU mean when it talks about safety? The use of border surveillance technology is often justified under safety pretexts; however, several examples show that it has instead been used to facilitate push-backs in the Mediterranean sea or to conduct enforced disappearances at external borders. Given that the Evros river is an extremely surveilled and violent area, it is clear that this approach to safety does not include migrants’ safety, nor does it guarantee respect for the human rights of all.

- What is the role of research in legitimising policies of border violence?

In the same way that biased research and pseudoscience has historically been used to justify racial discrimination, there is a high risk that EU’s funding of public research into border surveillance could lend a veneer of scientific objectivity to some of its violent migration practices, and policies. Tested across the EU, these programmes usually focus on demonstrating the systems’ accuracy, without questioning the problematic underlying assumption that migrant and racialised people are an inherent threat to Europe.

What European policymakers need to know — and do

Surveillance does not equal safety for all. While surveillance technology is deployed on security grounds, violence against migrant people continues daily. In addition, many of the EU-funded research projects testing and deploying this technology are doing so outside of any legislative framework, which further reduces accountability. EU policymakers must:

- Stop using EU public research funds for border surveillance testing programmes;

- Ensure transparency when the technology tested in any research projects is subsequently used in the field; and

- Commit to ending any inhumane treatment and violations of migrants’ human rights at Europe’s borders.

For any questions regarding this blog, please contact caterina@accessnow.org. If you or your organisation needs digital security support, please contact help@accessnow.org.

This article was first published here by EDRi memberAccess Now.

This is the second instalment of a three-part blog series. Catch up on part one here.

Contribution by: Caterina Rodelli, EU Policy Analyst, EDRi member, Access Now